In comparison with the relatively slow development of most mammals, fish have a much shorter lifecycle and so mature quickly. The incubation period varies for tropical fish eggs, but most hatch rapidly, because while still trapped in the confines of the egg, the young fish are too vulnerable to predators. Hatching generally takes place within 72 hours; if abnormally prolonged -because of low water temperature which slows the development of the fry – the eggs are more likely to be attacked by fungus. Under normal circumstances, unless the water is heavily contaminated, fungus is unlikely to be a significant problem, and only infertile eggs are likely to be affected.

The newly hatched fry

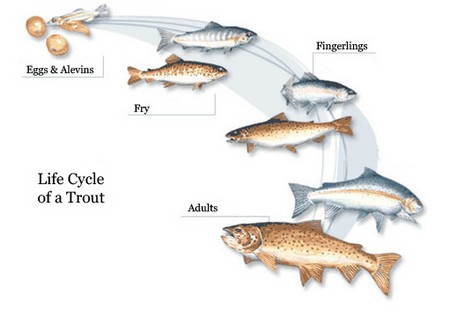

When the fry first emerge from their eggs, they still have the remains of the yolk sac on the underside of their bodies. This is a source of nourishment and is absorbed through the yolk duct which connects to the intestines. The young fish then remain mostly inert and hidden for several more days, until this built-in food reserve is used up. After this, they necessarily begin to swim freely and start seeking their own food.

At first, the fry feed on tiny organisms that are within easy reach in the water, gradually taking larger food items as they grow. Even in an aquarium where they are reared under identical conditions you will notice that some individuals grow at a faster rate than others. If this occurs, it is advisable to separate the larger fry, otherwise they may start to prey on their smaller companions.

Lifecycle and longevity

The lifespan of some fish may be a matter of just months, which obviously affects the speed of their development. In the case of ‘annual’ killifish, the fry must develop very rapidly. In the wild, these fish inhabit shallow pools that evaporate during the dry season under the hot sun, giving them only a brief period in which they can breed. If the opportunity is lost, the population will die out. These particular killifish, found in parts of Africa and South America, therefore mature within three months of hatching. They spawn as the water level falls, leaving their eggs encased in the mud at the bottom of the pool. The adult fish then die, but when the rains return, their eggs start to hatch, starting the cycle again.

Problem parents

In some cases, particularly with pairs that are spawning for the first time, the parental instincts of the fish are thwarted. Once the eggs have been laid, all may appear to be proceeding quite normally at first, but suddenly, for no apparent reason, before they have even hatched the adult fish eats them. Immaturity or excessive disturbance appear to be common triggers for fish that normally have highly developed parental instincts to neglect or consume their eggs or fry.

When this occurs, it is obviously upsetting, but before long the pair should lay again and will often go on to reproduce successfully a second time. Do not worry if, as the time for hatching approaches, you notice the fish nibbling at the eggs. Under these circumstances, it is more likely that the adults are helping their offspring out of the egg casings, rather than trying to eat them. Some cichlids set up ‘spawning pits’ where the young fry can be guarded until they are able to fend for themselves. Although it is not possible for the adult fish to protect all their offspring, they can care for a significant number in this way.

Small fry have less likelihood of surviving because they are inevitably more vulnerable to predators. Some of the largest fry produced by aquarium fish are those of the four-eyed fish (Anableps anableps), which are at least 2.5cm (1in) long at birth. Not surprisingly, females of this species usually produce no more than four offspring at a time.

Mutations

It is quite common for some of the young fish to be markedly different in appearance from the adults, and they are often less brightly coloured. In a large group of fry, there may well be a few individuals that are clearly malformed. Not all mutations are necessarily bad, however; particularly in the case of prolific livebearers such as guppies, there may be a variety of natural mutations to basic characteristics such as coloration and fin shape in the newborn fry.

By separating out these individuals for selective breeding, it may be possible to develop new strains over a period of time. The breeding system used for this relies on Mendel’s theory of genetic heredity. Each of the offspring will inherit one set of genes from each parent, so when one of the mutated individuals mates with a normal fish, the fry will carry the gene for the mutation, even though their appearance resembles the normal fish. At the next stage, if these individuals are paired together, a proportion of their offspring will bear the characteristics of the original mutant parent.

Careful breeding of this type has led to the wide array of colours now available, especially in the case of guppies and other species that reproduce very successfully. Unfortunately, problems may arise with selective breeding – for example, certain strains may die out due to infertility, possibly occurring as a result of pairing fish that are too closely related.