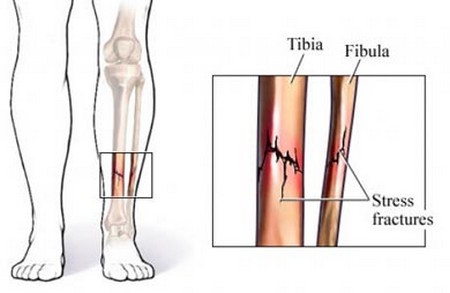

Stress fractures are tiny, often microscopic breaks in bones. The bones of the feet and shins are particularly affected. Symptoms include one or all of the following: dull ache, local tenderness, and swelling. Pressure applied to the site of injury also produces pain.

This is a classic injury of overuse. Exercisers who are logging too many miles, exercising too often, and exercising on hard surfaces are candidates for stress fractures. Surfaces that have little or no “give” or resiliency force the body to absorb more of the shock. This applies to joggers in particular because of the high shock of landing. Quality jogging shoes are a must, but they can absorb only a portion of the shock.

Women who are training heavily are susceptible to stress fractures, particularly if they become lean enough so their menstrual cycle stops, in which case the production of estrogen (female sex hormone) also stops. Estrogen protects the bones from thinning. A female runner who has had amenorrhea for a couple of years has lost a significant amount of bony tissue, and this, in combination with vigorous training, leaves her vulnerable to stress fractures. The risk of stress fractures for women can be reduced by cutting back on mileage and by not becoming so lean as to interrupt the menstrual cycle.

If a stress fracture has been diagnosed, rest is essential. The physician will advise when the person can return to physical activity. At that point, these people cannot pick up where they left off when they were injured. They should start at a low level and gradually increase the duration, frequency, and—last—the intensity of exercise.

Stretching properly before and after exercise is essential, as are walking and jogging surfaces that have some “give.” Preferred surfaces are artificial surfaces (such as those found on football fields and running tracks), flat, grassy surfaces free of holes (such as public parks and golf courses), and cinder running tracks. Motorized treadmills offer a resilient surface for walking and jogging.